The Three Fundamental Ways Walls Manage Water: Transcript & Graphics

This is the transcript and graphics from "The Three Fundamental Ways Walls Manager Water" course video. To watch the full video, please visit our course article.

This may seem basic to a lot of professionals, but in my experience, this – right here – is where a lot of people – even those with a lot of design and construction experience – first go wrong in either designing to avoid failure or diagnosing failure after it has occurred. Walls manage water in three ways: Storage … WRB and Drainage… and Exclusion. We’re going to discuss each.

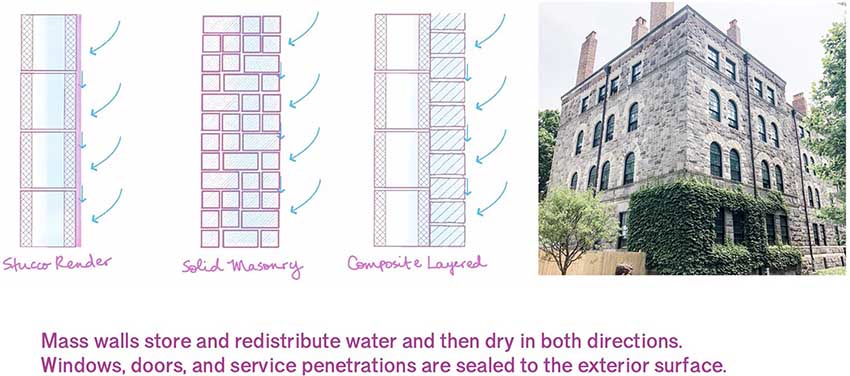

The Storage approach involves the wall absorbing water, redistributing that water, and then releasing it by drying. This is how mass walls manage water. The mass wall gets wet. It has an enormous capacity to store and redistribute that water, and then it dries in both directions. This works very well because mass walls are built out of materials that aren’t moisture sensitive. These walls have a long history of performance and indeed many of the world’s most beloved buildings manage water in exactly this way.

The classic example of this kind approach to water management is the solid masonry wall. Masonry walls with stucco renders are also common as are more modern composite walls with combinations of different kinds of stone and block.

These walls are very durable. And they are heavy. They literally weigh a lot. They also tend to cost a lot, in part because they are so heavy.

Windows, doors and service penetrations are sealed to the exterior surface.

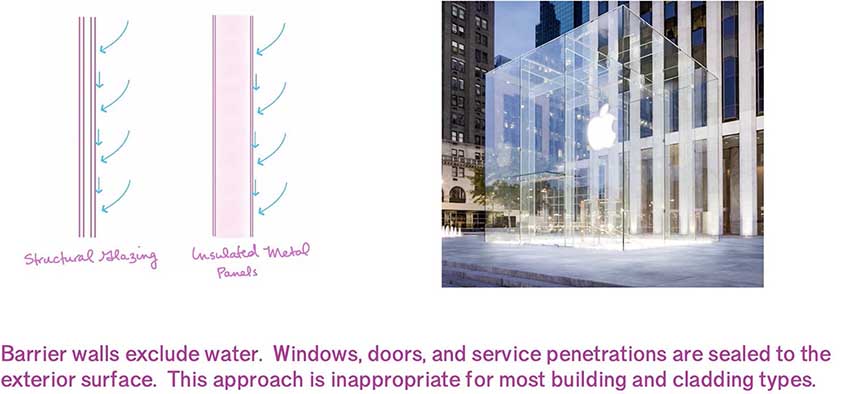

The second approach to water management in walls is Exclusion. We call these walls barrier walls or perfect barrier walls. Windows, doors and service penetrations are sealed to the exterior surface.

This is the least common approach to water management in walls and also the most tricky. Structural glazing works this way — like the Apple Store — and insulated metal panels walls often work this way.

There is nothing wrong with this water management strategy — it’s application is very narrow though. Most of the time it’s simply not realistic to create a perfect barrier for water, and still build the type of building we want to build out of the type of materials we want to use. Many of the most popular building materials just don’t lend themselves to perfectly blocking water and doing so throughout the entire service life of the building.

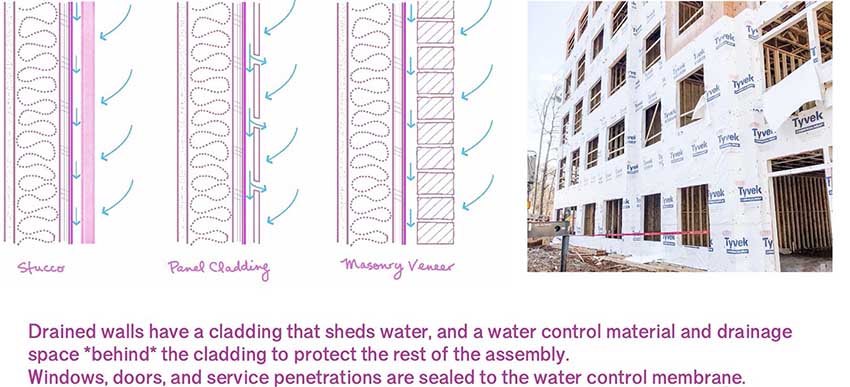

The third approach to water management in walls is WRB and Drainage. Drained walls have a cladding that sheds water, and a water control material and drainage space behind the cladding to protect the rest of the assembly. The building code calls the water control membrane a WRB or water resistive barrier and we seal windows, doors, and service penetrations to that water control membrane.

The idea here is that we can build lightweight framed walls — as opposed to heavy, solid masonry walls — and we can build our lightweight framed walls out of moisture sensitive materials like wood ... if we protect those moisture sensitive materials from excessive wetting by having a cladding that sheds water and some kind of membrane behind the cladding to protect the moisture sensitive parts behind it.

This water management approach is the standard approach in North America. And it’s part of why building is so inexpensive here. Framed construction out of lightweight moisture sensitive materials really is an extraordinary innovation. There are trade offs! There are always trade offs. But this really is wonderfully clever.

The trouble really comes when we mistake one of these three water management strategies for another. We tend to not like the results when we treat a drained wall like a mass wall or a perfect barrier wall.

It’s very important to point out here that this represents a really significant difference in how a professional approaches water management in design and how lay people — including many of our clients — approach water management. Most of our clients assume that there’s only one approach to water management in walls and it’s Exclusion. They don’t understand how mass walls work. They don’t understand how drained walls work. Which can make communication difficult.

A lot of people want to know, what’s the best water management strategy? And that’s really not the right way of looking at this. All three of these three approaches are just fine. They will all work in all climates. They don’t all work well with all materials though. And different architectural styles lend themselves better to one approach or another. But these are value-neutral approaches. The question isn’t which one is better overall, it’s which approach will work better in the context of a specific project with particular aesthetic and performance objectives.

On a related note, I’d like to touch on a huge misunderstanding related to drained walls but it’s really true of all three wall types. And that is that each of these walls is practicing a system of water management. We like to say that we think of buildings holistically and like a system, but in a very practical sense that often breaks down because of how we actually go about building our buildings. We assign the different parts to different trades, different subcontractors, different specification sections… and they fall under different sections of the building code. What this often means is that we think of water management as being the job of the water control membrane. And that’s true. The water control membrane does manage water. But it’s only one element in our system.

When it comes to drained walls, the water control membrane cannot do its job without the cladding, which sheds water, and the air space between the two, which we include for drainage and ventilation. There is this idea that the water control membrane should function independently, but it doesn’t. And it was never designed to work independently. The water shedding cladding and space for drainage and drying are just as much a part of the water management system as the WRB. It is simply not the case that we include a water control membrane because the cladding failed to keep the water out. The cladding was never designed to work that way!

Where I see people make this mistake most frequently is in attributing building failures to poorly installed cladding. Now, what I’m about to say shouldn’t be considered permission for poor workmanship. But it’s important to be clear that we don’t include a water control membrane in our walls as a redundant feature, as back-up in case the cladding fails. It’s just one element of a system.

And this leads me to the most important part of all this: when we design walls we are not engaged in water proofing. We’re engaged in water management.

For water infiltration to be problematic, the wetting a wall experiences must exceed its capacity to store and redistribute water for long enough to damage the materials that compose it.

This point is absolutely fundamental to building science. And it’s really the context that helps us understand our three water management strategies better. Mass walls work because their capacity for safe storage is so high. Perfect barrier walls work because we essentially eliminate wetting. And drained walls work by walking that tightrope between wetting, drying, and safe storage. Even the moisture sensitive parts of the wall behind the WRB get wet. Routinely. But they don’t get wet enough, for long enough, to cause damage. And that wetting is not a failure. It’s a feature. It is how we’ve designed the system to work. And it’s pretty cool.